Army Surplus

The things that outlast the uniform.

My Drill Sergeant had an alter ego named Dick Cheney. You’d know he’d switched when the front of his campaign hat was pulled down to his eyebrows obscuring his face except his mouth, which was usually barking orders.

At first we all thought it was some kind of gag, a Jekyll-and-Hyde joke at our expense. But we soon learned otherwise. Dick Cheney appeared when the barracks were deemed unclean, or the corners on a bunk not tight enough. He materialized from thin air when we were caught with contraband. He sprung from the shadows when you fell asleep on fire watch. Before long, Dick Cheney loomed over our platoon, our omnipotent overlord.

Memories of him and the time I spent under his watchful eye surfaced the other day while prepping for a trip. It was late and I was in a frenzied last-minute packing sprint — the one that builds from days of procrastination and poor organization.

I was digging around in the bottom of the big plastic Stanley foot locker that houses my fishing kit — the same one that, coincidentally, held all my military gear for a year in Afghanistan — when I found my Army-issue E-tool (Entrenching Tool, a.k.a packable field shovel).

I pulled it out and turned the loam green plastic case over a few times in my hands. It was heavier than I remembered. I opened it and a shower of loose dirt and a few stones chattered onto the cement floor of my garage. Seeing that I had put it away dirty tickled my long-dormant soldier brain and manifested as full-blown embarrassment. Suddenly, I was Private Sotak again, red-cheeked and looking over my shoulder for a Drill Sergeant on the prowl.

The best of trout season in the Northeast is generally bracketed Memorial Day and Veterans Day, and I often find myself going into, and coming out of those fishing months with the military on my mind. But finding that damned shovel got the wheels turning early.

I found I kept coming back to the gear that’s stayed with me through the years, pieces of a former life that continue to serve long after their expected lifespan. Military issue equipment is often lauded for its robustness, and even, surprisingly, its status as a fashion accessory.

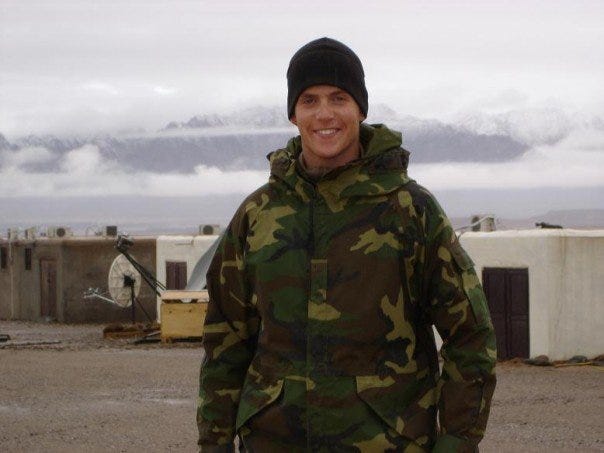

I accumulated a fair amount of gear during the decade I spent in the Army, and today it comprises a sizable share of the equipment I reach for when I prepare for a trip to the woods. My woobie (a.k.a. an insulated blanket that doubles as a poncho liner) goes on nearly every trip, the woodland camo GORE-TEX rain parka that I wore all through deployment and is still the best rain jacket I own. My favorite camp shorts are camo cutoffs that once belonged to one of the first uniforms issued to me, and so on. There’s a couple of rucksacks, a pair of foam sleeping pads that double as mats for roadside de-wadering, and a heavy fixed blade field knife that brings more peace of mind than purpose when bivouacking in bear country.

Half of my surplus military-issued equipment is from the era of woodland camouflage, an antiquated pattern deemed ineffective in the era of desert combat of which I was a part. The other is from the Army’s response — UCP (Universal Camouflage Pattern, a.k.a the first Army digital camouflage) — that was supposed to revolutionize camouflage, and was itself replaced after only a decade of use. (Much like I was.) Most now lives in green duffle bags in the back of the garage patiently waiting to be deemed useful, perhaps one day even collectible.

A few years ago I was looking for a simple solution for carrying a couple of small fly boxes while fishing with a pack and finding nothing that I liked, I decided to make one. I knew I wanted it to be fashioned from a rugged material that would hold a shape, so I grabbed one of those old duffle bags and got to cutting. From other gear I pirated plastic clips, a black YKK zipper, and some OD-green hook-and-pile tape (a.k.a velcro) and took the amalgamation to the only person I know who could help me turn it into something: my mom.

She might have given me a funny look when I dropped the armful of surplus scraps onto her dining table, but didn’t miss a beat helping me sew them together. Perhaps she saw catharsis in the chopped up relics of my previous life. And after a few short hours she’d turned them into something wholly new.

I call it the Rip Cord: a small chest pack with room for two small fly boxes, some tippet spools, nippers, and a pair of forceps. Whenever I use it I think about its metamorphosis and smile. If Dick Cheney could see me now.

The Army wasn’t fun, but it made sense to me. I appreciated that there was a manual for everything, a methodology that everyone agreed on and was, for all intents and purposes, the way. I gravitated to the notion of preparedness, training for the most remote possibilities just so you’d have an inkling of what to do when it happened. I liked the structure, the value system, the way that some things were universally understood and observed, even if they were, at times, disagreeable.

One of the things that draws me to fly fishing is the sense of community, the existence of a unique culture. I like that we share a history that is at times absurdly antiquated and yet still so intrinsically linked to why and what we do today. There’s camaraderie, in the best and worst of times, and moments that create unlikely bonds with total strangers stronger than those of your own kin. You’re routinely humbled by nature, and reminded what the human body is capable of when the right motivation is applied. For me, fly fishing recalls what I liked best about the military.

Veteran anglers too, like soldiers, possess an assuredness of action that comes with time in the field, knowing when to strike and when to watch, and wait. And they aren’t mouthy about their exploits. Rather, they respond to braggadocio with quietness; they know the loudest guy in the room is the one most full of hot air. They know that while being lucky often looks like being good, being truly skilled at one’s craft is achieved only when unyielding failure is met with unwavering spirit.

Good gear is hard to get rid of, especially when it's imbued with the memories of a former life filled with discipline and danger. Perhaps that I still reach for my old Army equipment when I pack for a trip is apropos of something, but what, I don’t know. Mostly I’m content to continue to add some honest wear to the gear that’s accompanied me for two decades, and continues to serve me so selflessly.

Every so often, when I’m hiking into a remote stretch of water with a pack, I feel the urge to hold my fly rod at the low-ready as if I were on foot patrol. Or catch myself walking up to a run all soft-footed and bent-knee, muscle memory charting a path to this new kind of ambush.

And on tired-leg treks back to faraway vehicles I feel the urge to sing cadence, and sometimes do, playing call-and-response with my memories, and the birds.

Great post. I was gifted one of those same Gore-Tex jackets when I was 12 I think wore it until I was 30. Now I’m debating buying one again.